In the fast-paced world of manufacturing, production leaders face a constant influx of data. However, simply acquiring data is not enough to drive operational excellence. To make informed decisions and identify root causes, leaders must strive for a deep understanding of daily operations. In this blog post, we will explore the critical differences between data acquisition and true understanding. Additionally, we will provide practical strategies for manufacturing leaders to enhance their comprehension of daily operations.

1. Overwhelming Data: A Barrier to Effective Processing

In today’s manufacturing landscape, we are inundated with more data than we can effectively process. The sheer volume of information can overwhelm leaders, making it challenging to extract meaningful insights. Leaders must recognize that data alone does not equate to understanding. Instead, it serves as a foundation for deeper analysis and interpretation.

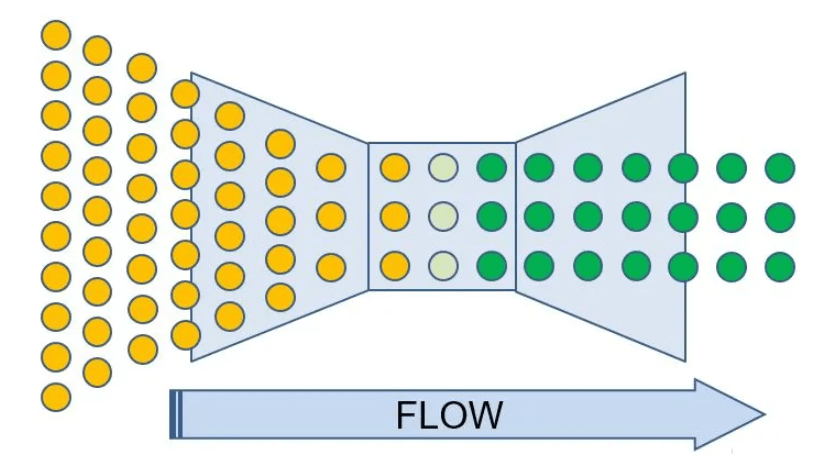

2. Grasping the Root Cause: The Key to Operational Constraint

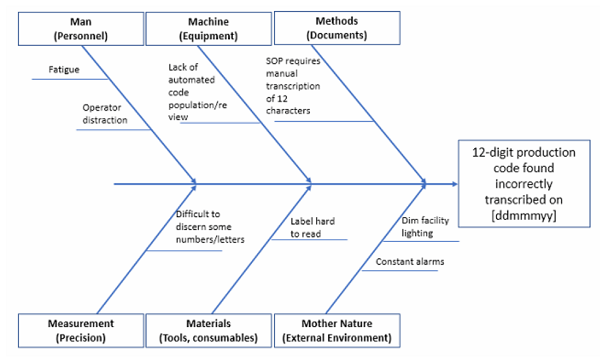

To overcome operational challenges, leaders must fully understand the problems they encounter. Superficial knowledge of symptoms or surface-level analysis is insufficient. True understanding requires delving into the root cause and uncovering the underlying factors that contribute to constraints or inefficiencies. By addressing the root cause, leaders can implement targeted solutions and drive sustainable improvements.

3. Data vs. Understanding: Bridging the Gap

Recognizing the distinction between acquiring data and reaching a comprehensive understanding is crucial. Mere data acquisition involves collecting information without necessarily gaining insights. True understanding, on the other hand, involves analyzing data, recognizing patterns, and contextualizing the information. It is a cognitive process that leads to meaningful comprehension and informed decision-making.

4. Differentiating Data Acquisition from Understanding

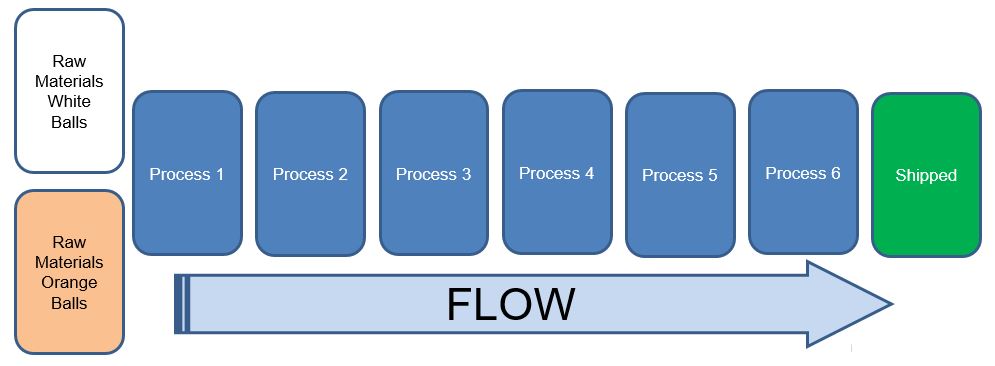

To shed light on the disparities between data acquisition and understanding, let’s explore the key differences:

- Depth of Analysis: Data acquisition involves collecting information at a surface level, while understanding requires diving deeper, analyzing patterns, and uncovering insights.

- Contextual Understanding: Data acquisition may provide isolated facts, whereas understanding involves comprehending the context, interrelationships, and broader implications.

- Interpretation and Synthesis: Understanding necessitates interpretation, synthesis, and connecting the dots between data points, enabling leaders to derive comprehensive insights.

- Application and Problem-Solving: Data acquisition lacks the ability to apply knowledge to practical situations while understanding empowers leaders to address complex problems effectively.

- Decision-Making: Understanding enables leaders to make informed decisions by considering various factors, weighing consequences, and assessing the long-term impact.

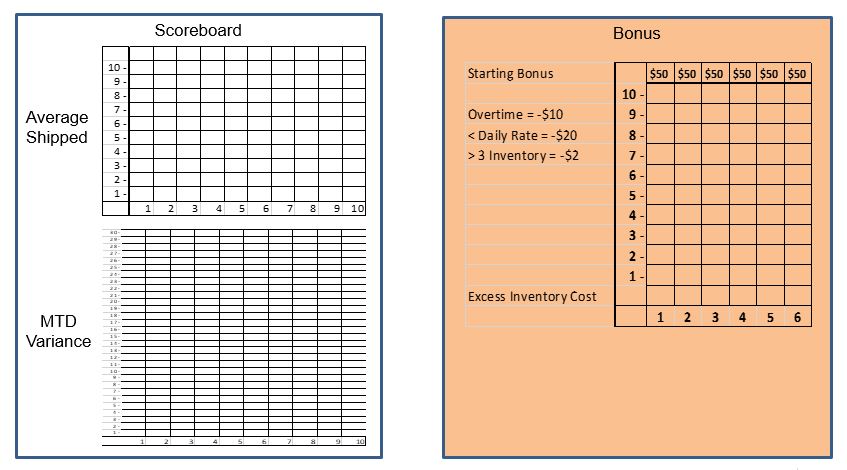

5. Strategies for Improving Operational Understanding

Manufacturing leaders can enhance their understanding of daily operations by implementing the following strategies:

- Embrace Gemba Walks: Engage in regular visits to the shop floor to observe operations firsthand, ask questions, and gain a deeper understanding of processes and challenges.

- Foster Cross-Functional Collaboration: Encourage collaboration between different departments and teams to gain a holistic view of operations, leverage diverse perspectives, and foster knowledge sharing.

- Invest in Data Analytics: Utilize advanced data analytics tools and techniques to analyze large datasets, identify trends, and uncover meaningful insights that can drive informed decision-making.

- Continuous Learning: Encourage a culture of continuous learning by providing training opportunities, promoting knowledge-sharing sessions, and encouraging personal development.

- Develop Mentoring Relationships: Establish mentorship programs where experienced leaders can guide and share their insights with emerging leaders, facilitating knowledge transfer and deepening understanding.

Conclusion

In manufacturing leadership, true understanding surpasses mere data acquisition. It drives effective decision-making and operational excellence. By recognizing the differences and prioritizing insights and root causes, leaders can enhance their understanding of daily operations. Embracing strategies such as gemba walks, collaboration, data analytics, continuous learning, and mentoring relationships empowers leaders to unlock hidden potential and drive transformative change. With a deep understanding, manufacturing leaders navigate complexities with confidence, achieving lasting success.